This is the first of a series of posts on the Pitcairn petroglyphs. Thanks to Pauline Reynolds we now know that Pitcairn was called ‘Hitiaurevareva’ in Tahitian tradition. On the Marquesas, it was known as ‘Mata ki Te Rangi’ – eyes to the sky or edge of the sky.

This journey of ideas began when I was working alongside Dr Te Huirangi Eruera Waikerepuru, a highly respected Kaumatua who championed Reo Māori being an official language of Aotearoa. He always maintained there was a strong connection between early Māori and Egypt. There is also oral tradition on Fiji. I’ll get to those in the next blog, but this first one asks the question: is it technically feasible that such a connection could have taken place?

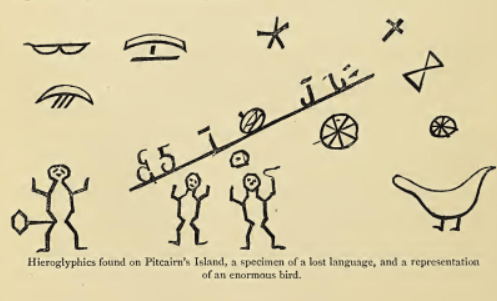

To tell a full story of the petroglyphs (remember it is only a story, a kind of best guess), it is first necessary to have an understanding of where navigation was at in say, 100 BCE. There’s a reason for this date, which I’ll go into later. The image immediately above comes from a book published in 1870 by the Reverend Richard Taylor. The photograph at the top was taken in 1928. The 1870 drawing is therefore a summary sketch, rather than strictly documentary. Let’s now take a look at navigation in Moana (Polynesia is becoming unfavoured as a description) over this period.

Moana/Polynesian navigation

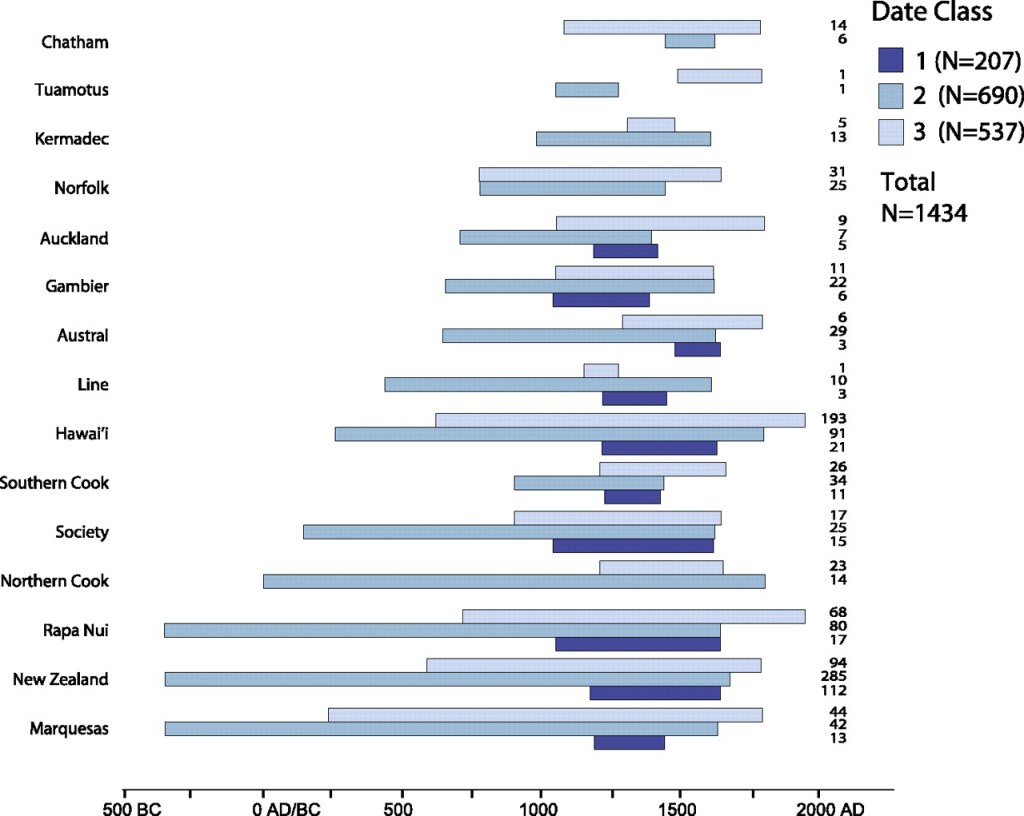

Radiocarbon dating guide to Polynesian exploration of Te Moana Nui

If you look at this image:

What we have is a list of islands of Te Moana Nui down the left hand side. Along the bottom is a timeline that goes from 500BCE to 2000CE (it uses the old ‘BC’ and ‘AD’, but they mean the same thing).

The blue lines are different types of samples used to radiocarbon date material found at known cultural sites. Here is a link to the source article. The dark blue lines are Class 1 samples, the mid-blue lines are Class 2, and the light blue lines are Class 3. Class 1 samples are the ones scientists like – they are the most certain.

If you look at the longest Class 2 lines, we have radiocarbon-dated samples on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Aotearoa New Zealand, and the Marquesas at around 300 BCE. What this most likely means is that someone in an ocean-going va’a (waka in Māori) landed at these locations, pulled the va’a onto the beach, and made a fire. Now a driftwood log could be up to 200 years old. This is why Class 2 items are less reliable. It is also why I picked the date ‘100BCE’ as this would account for any deviation in the samples.

So this is evidence that Moana voyagers knew of these islands between 300 BCE and 100 BCE. This is more or less the spread of eastern Te Moana Nui. There is confirmation of the date of 300 BCE for the Marquesas in the Rarotongan oral record, found in this book. The islands were not settled at this time – that occurred much later, around 1190-1290 (the dark blue lines of the chart above).

The other thing important to comprehend is that traditional navigators (Kaiwhakatere in Māori, ‘Aifa’atere most likely in Tahitian) understood the Earth was curved, the consequence of this is understanding leads to the idea of Earth being a ball in space. This is because they would see islands coming over the horizon. First there is a mountain top, then the whole mountain and land, and slowly the island grows bigger until you reach it. As it happens, traditional Kaiwhakatere (the same word is used for navigator or navigation) visualised the va’a as stationary and what they were doing was pulling the island toward them. It is truly astonishing to think of ocean going va’a covering such vast distances at such an early time. Next we turn to looking into knowledge in North Africa over the target period.

North Africa/Libya/Egyptian knowledge

The population landscape of Northern Africa 300BCE

Firstly, during this era of 300-100BCE, the region of the whole of northern Africa was one area seen above, which had an area designated the home of the Berbers and another for Libyans, with a Libyco-Berber script. The area for the Ptolemaic Kingdom that we associate with Egypt was squashed in the upper right of Africa. A large swathe is designated to ‘Saharan Pastoral Nomads.’ In those days, there were no passport controls or country boundaries as we know them today.

If you look at this page from the British Museum, there is some thinking that the Libyco-Berber script dates to around 300BCE – check out the text after the fourth image. Some of the images in that page are rock paintings and some are rock ‘engravings’ or petroglyphs. Having attained an idea of populations in North Africa at this time, lets take a closer look into knowledge about the Earth.

The father of geography determines south and north pole, tropics and equator

Eratosthenes of Cyrene is now known as ‘the father of geography.’ Eratosthenes was head of the library of Alexander, from around 255 BCE. Based on reading scrolls in the Library, he put together the notions of a cold pole at the top and bottom of Earth. Eratosthenes also created the ideas of the tropics and the equator. So we have a spherical Earth and he also made a calculation of the size of the Earth, which has proved fairly correct. It can only be assumed that Eratosthenese read of mariner accounts of a frozen land to the south and another to the north, and differences in the regions of the tropics related to weather. Unfortunately the scrolls of the library were all destroyed before 800.

At this time – around 300 – 100 BCE, Greek was the language of astronomy, and Eratosthenes spoke Greek. Archimedes (also Greek) was contemporary with Eratosthenes and is believed to have created around 300BCE the Antikythera device, which could calculate the 464 year orbit of Venus among much else. Archimedes deposited all his scrolls in the Library of Alexandria shortly before Eratosthenes became Head Librarian.

What these first two sections tell us is that the knowledge of Earth from both the Te Moana Nui side and the North African/Libyan/Egyptian side was fairly complete in the period 300-100 BCE and concurs with what we know today. This is why the first of these blogs starts with the question of whether such voyaging was possible in ancient times. That the knowledge of Earth was known at this time is extraordinary, and it is required to navigate across Te Moana Nui. This is a revelation in our understanding of navigation in Te Moana Nui and North Africa. We need to get used to the idea that most likely, multiple trips were going on long before previously supposed.

What does this mean for the petroglyphs?

Well, where this is going is that in some of the translations around, which Meralda Warren referred to on the Facebook group, talk of an Egyptian/Libyan script being used in the petroglyphs. But before we go there, let’s check to see what is in the oral heritage of Moana peoples in regard to a possible ancient connection between North Africa and islands of Te Moana Nui. That is the subject of the next post in the series.